Why Standard Work is the “Secret Weapon” of the Best Lean Companies

In this blog, we’ll provide a solution to a common problem across all industries: insufficient standardization, leading to quality issues and inconsistent throughput rates. Specifically, we will talk about an advanced form of standardization called standard work.

What is Standard Work?

Standard work combines industrial engineering and operator knowledge to define in practical form how to use labor, materials, and machines in the most efficient way.

While you may at first be a bit shocked by the level of detail involved, it is a proven solution. In fact, people at Toyota call standard work the company’s “secret weapon.”

The key is to describe the job so that anybody can do it in the best known way. When you perform work in a repeating, rhythmic cycle, learning and doing the work with consistency becomes much easier. In turn, consistency makes it easy to discover and measure deviations, and deviations make it easy to identify problems. When the problem is well defined, it is easy to improve.

Thus, standard work is not just a way to achieve the best performance consistently; it’s a way to continuously improve. The ultimate goal when you implement standard work is to teach operators to approach their work how an industrial engineer would.

What’s the Difference Between Standard Work and Standardized Work?

You will often hear the two used interchangeably, but there is a difference between these terms.

Standardized work applies to work that is entirely made up of cyclical repeating work. Each cycle has the same duration (the same work content). An example would be an operator working in an assembly or machine cell. This is sometimes called “Type 1.”

Standard work applies to work that has varying duration (different work content). An example is a car assembly line where no two cars have the same options and therefore each car requires a different time. This is sometimes called “Type 2.”

Standard work that is not repeatable in sequence or in work content is referred to as “Type 3.” An example is material handling or warehouse picking.

Why Standard Work is Necessary

It’s a sure bet that in most companies, if you observe workers performing the same job, each person will do it a bit differently. Whether this is because they were taught that way or developed their own preferred method is irrelevant. What matters is that it will make it very difficult to involve operators in continuous improvement. Let’s explore why.

Solving problems consists in finding ways to close the gap between a current state and a target state. If people can’t agree on what the current state is, needless conflicts and misunderstandings will result. In standard work, everything is specified, down to the path taken as you walk from work element 1 to work element 2, and how many parts of work in process (WIP) are to be found at specific locations.

In effect, standard work removes the noise and lets the signal come through loud and clear, helping the team understand the problem before solving it.

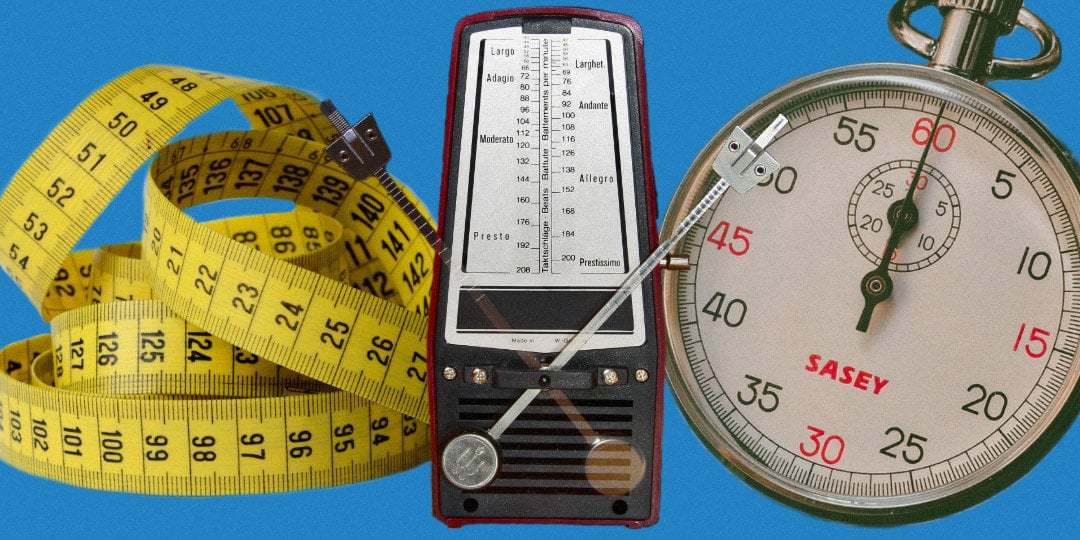

Standard work defines, for a given takt time (or range of takt times), the exact sequence of work elements a person must perform to complete a job, as well as the location and quantity of WIP to ensure there are no waiting times. To understand why it’s formatted in this way, remember that in Lean manufacturing we want to set cycle times (capacity) as close as possible to the takt time (demand). In this way, the quantity of resources used to meet demand is minimized.

As we describe what standard work looks like, keep in mind that it is specifically designed for Lean production, with operators working on one product at a time through the process, with some walking involved.

How to Start Using Standard Work

There are three documents that form the core of standard work. In many cases, you’ll need an additional two.

To get started with standard work, create the following:

- A description of the sequence and timing of operator tasks within the cycle, combined with the machine cycles if applicable.

- A description of the layout of the work area, with the exact path followed by the operator and the location of standard WIP, often called a “Standard Operations Layout.” This often appears on the same sheet of paper as the sequence and timing information above.

- A description of how to do the tasks. This is called the Standard Work Instructions, or simply “Work Instructions,” and it incorporates the operators’ deepest knowledge of how to produce quality, maintain safety, and be productive in the form of “Key Points.” This document belongs to the operators. Engineers provide the technical requirements, but rarely get involved after that, unless the requirements change.

The following two documents are also helpful:

- A description of our capacity to meet takt time, in the form of a “Capacity Sheet,” “Takt Time/Cycle Time Bar Chart” (TTCTBC), or “Yamazumi Chart” (which is a TTCTBC showing the tasks of operators working in an assembly line). This document is used for analysis of the process. It helps us identify bottlenecks, lack of balance between process steps, and in some cases shows that we do not have the true capacity to meet demand.

- A tracking of whether we are able to meet the standard consistently. This can take many forms: hour-by-hour boards, andon systems, process confirmation forms, and electronic counters for example. Tracking is used after the introduction of standard work to drive continuous improvement.

Where to Start with Standard Work

Don’t let the potential complexities of standard work slow you down. Instead, view the standard work documents and practices as a toolkit for continuous improvement and identify a starting point that makes the most sense for your goals.

What should you do if you have no Lean production in place? While it would make no sense at all to use a standard work combination sheet or a standard operations layout when an operator is stationary, you can always start by creating a detailed work instruction.

Just having the cycle broken down into work elements, defining the exact sequence of work elements, and adding the key points that make or break quality, safety and productivity requirements will be a great way to get started and identify potential improvements.

A tool that might help you in this process is digital work instructions. You can see our roundup of the best digital work instruction tools for tips on how to choose a system that works for you.

For more information, visit our Lean Center of Excellence Homepage or our homepage for Continuous Improvement, Operational Excellence, and Lean Professionals.

Previous Posts

Trump 2.0 Week 12 Recap: Discussing The Reciprocal Tariff Pause, The Escalating Trade War With China, and More

The Future of Manufacturing and Logistics

Create a free business profile today to explore our platform.